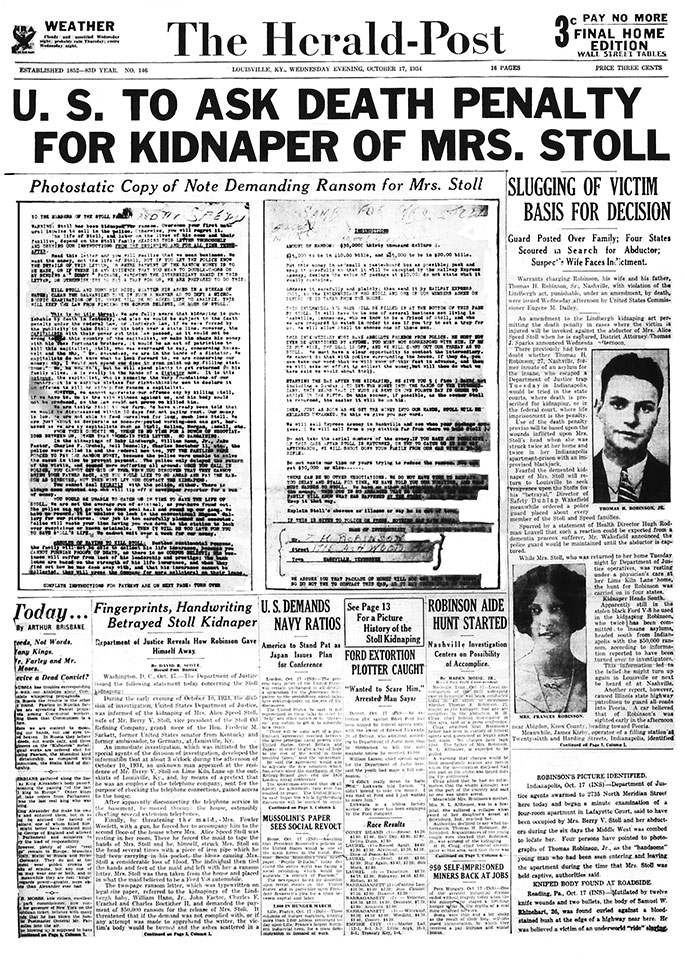

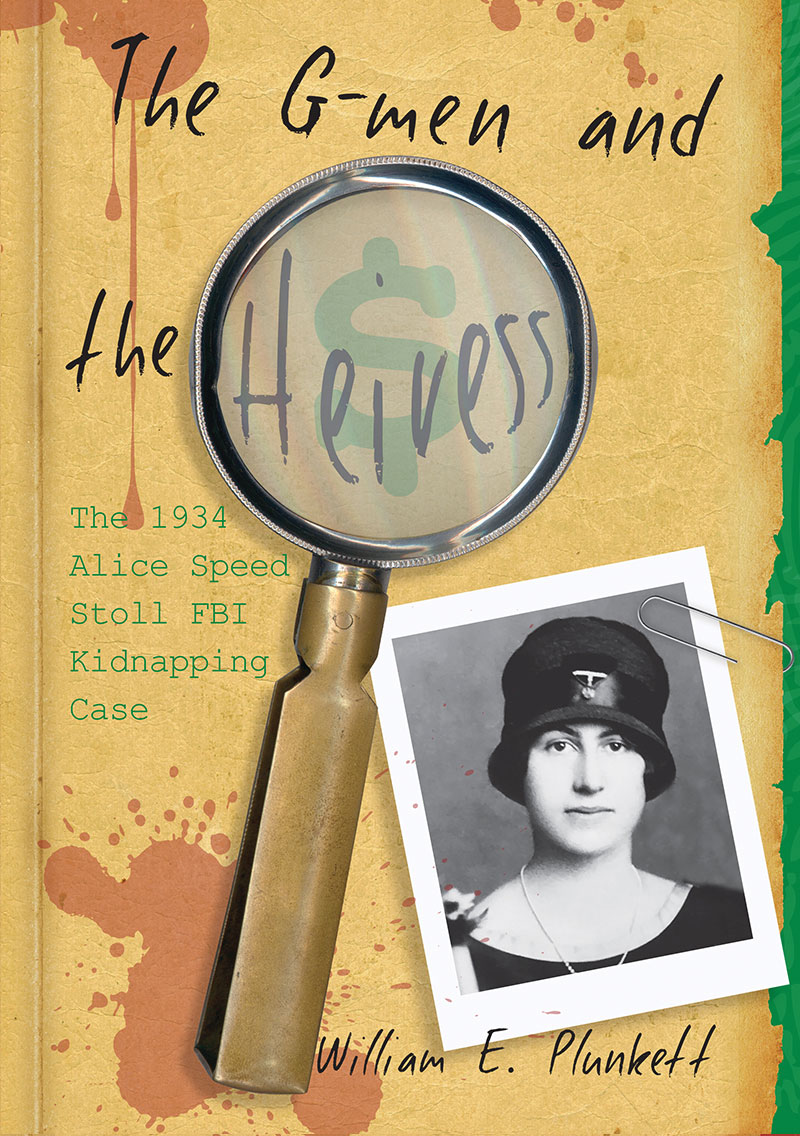

The G-Men and the Heiress: The 1934 Alice Speed Stoll FBI Kidnapping Case

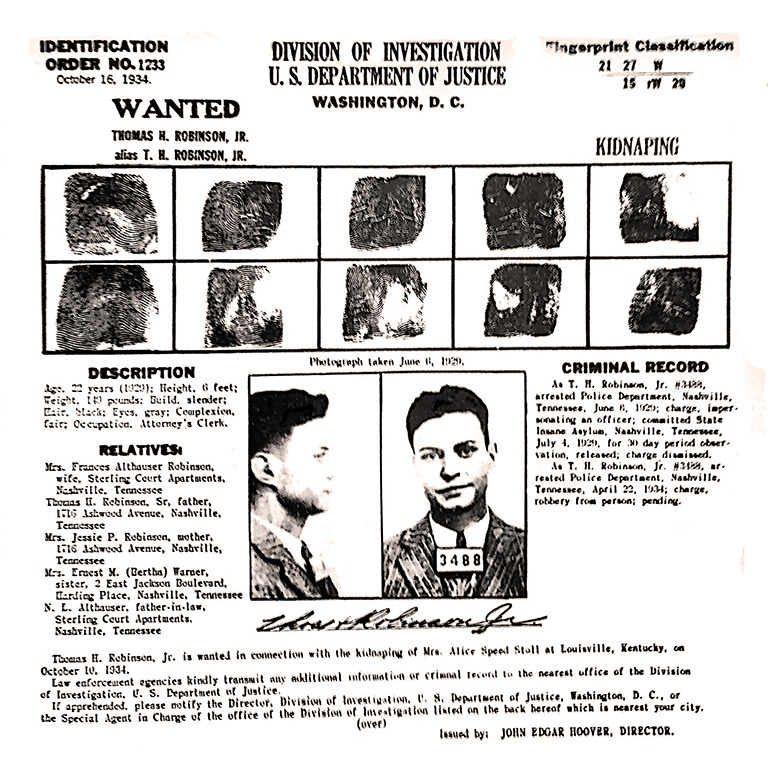

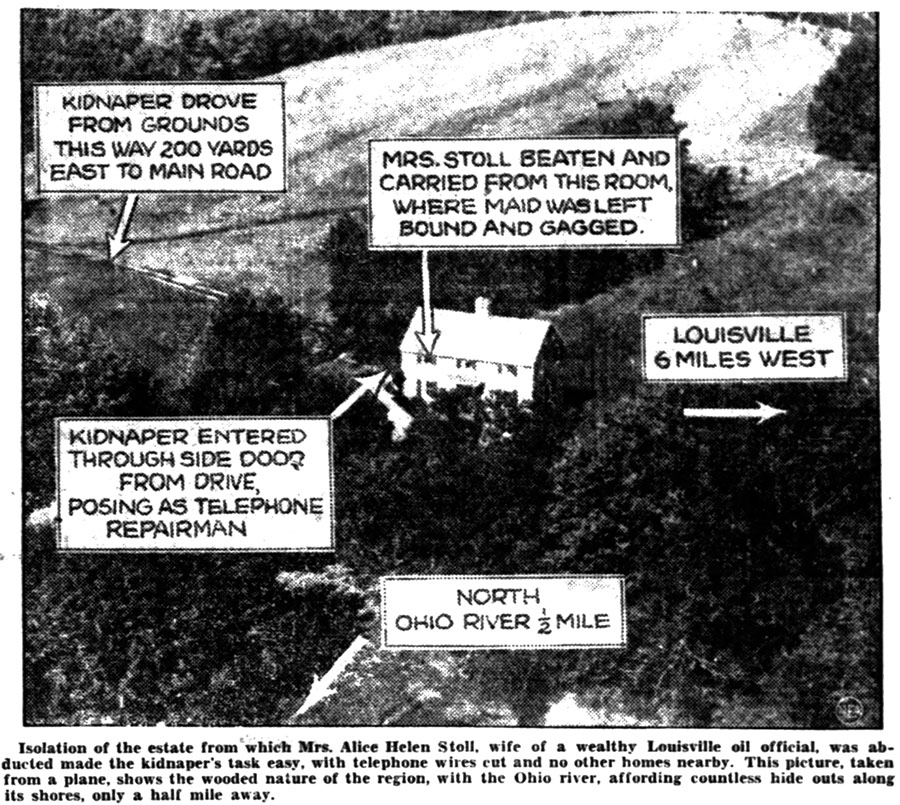

The kidnapping of Louisville socialite Alice Speed Stoll and 18 month pursuit by FBI for her captor.

By William Plunkett

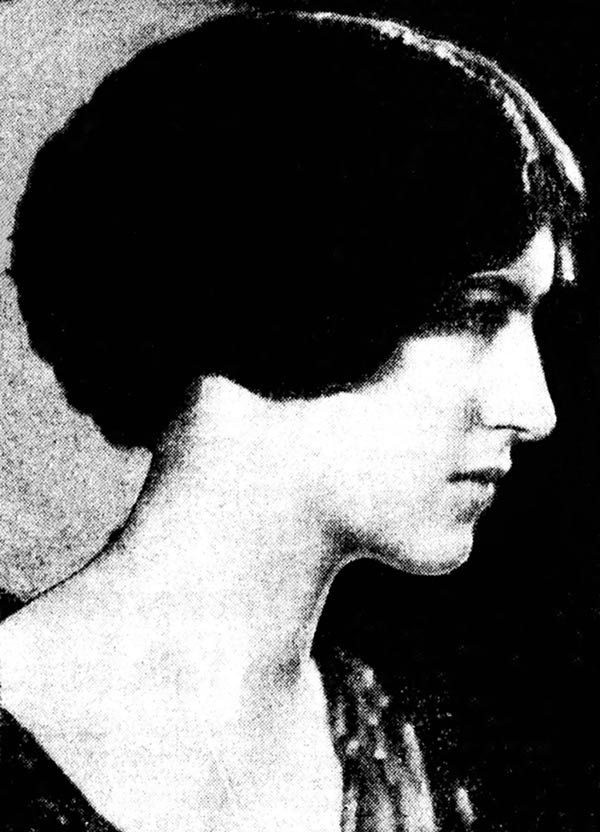

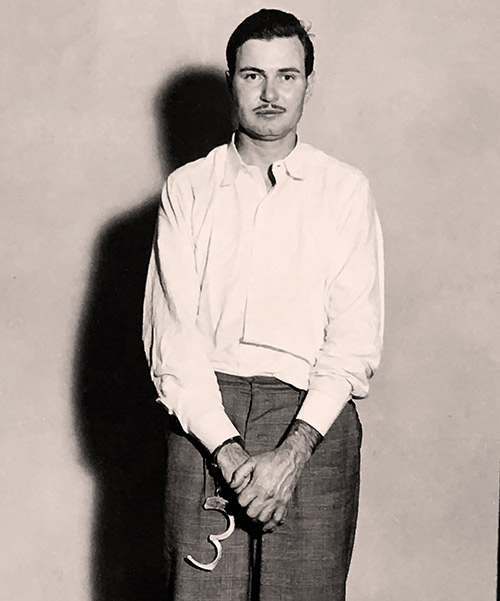

Alice Speed Stoll’s kidnapping wasn’t as famous as that of the Lindbergh baby, but in its own peculiar way, it was just as riveting. It featured a beautiful socialite, a troubled perpetrator tormented by his own inadequacies, a cross-country chase, prison escapes (including one from death row), an interminable (and plucky) jailhouse defense, and the efforts by America’s fledgling crime-fighting organization seeking to establish itself. Like the Lindbergh case, it, too, made The New York Times. (The Times labeled Robinson “insane,” which ultimately proved too easy a designation for someone so torturously complex.) Louisville Magazine, as recently as 2016, called the Alice Stoll case Louisville’s “crime of the century.”